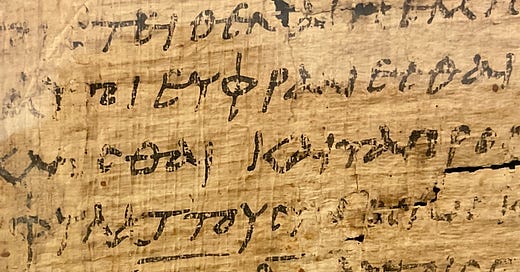

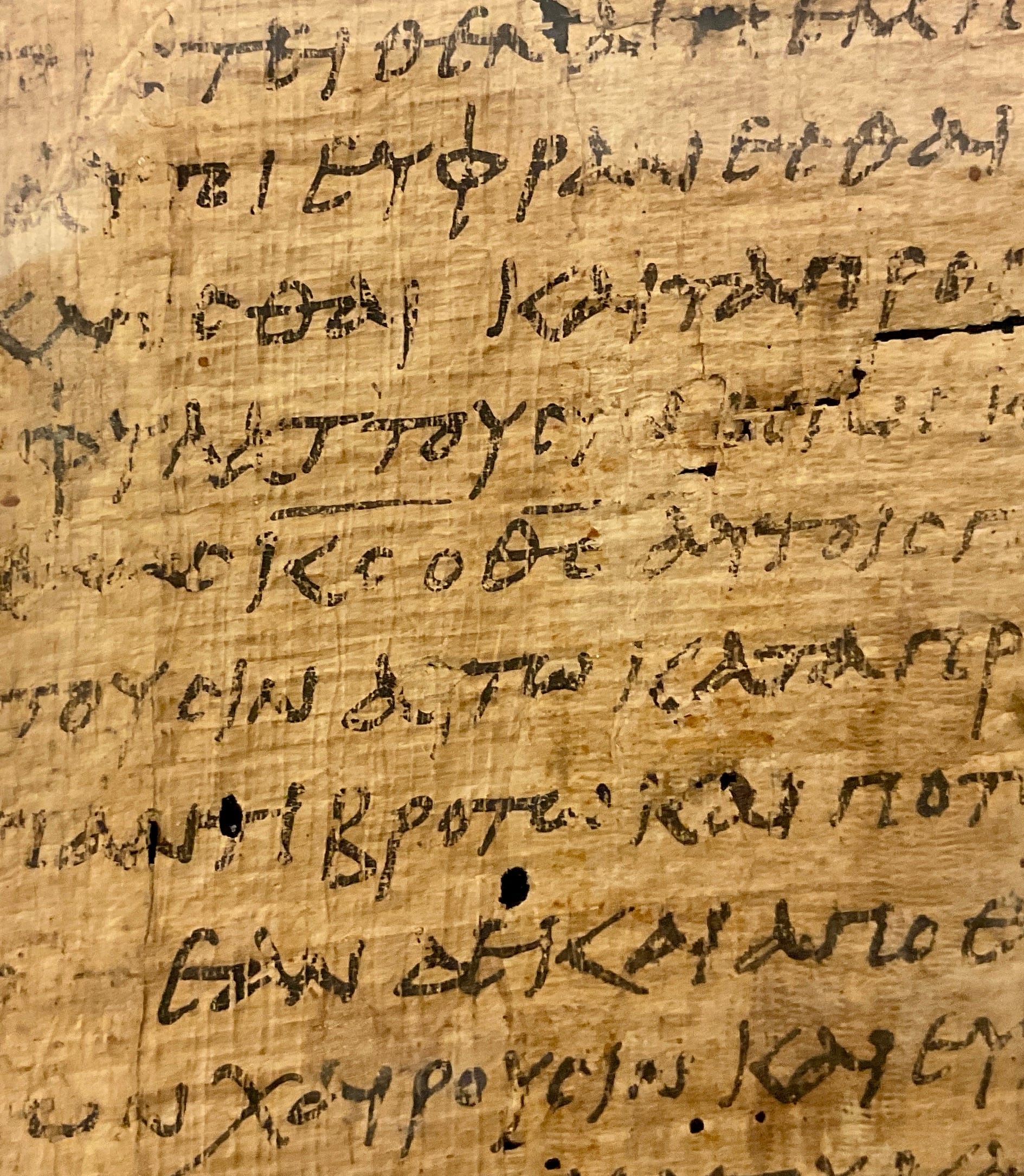

Aristides of Athens as Ecclesial Apologist: Syriac Translation, Greek Papyri, and Armenian Texts

The final installment of chapter 1 of my dissertation!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Apologetics Newsletter by Timothy Paul Jones to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.