What the Natural World Can—and Can’t—Do

If science and Scripture seem to be in conflict, it’s probably because someone is trying to make one or both of them do something that they weren’t designed to do

A few years ago, during the week leading up to Easter, the Secular Student Alliance at University of Louisville invited me to one of their meetings. They asked me to talk about the topic, “The Resurrection of Jesus: Myth or History?”

There aren’t a lot of believers in the resurrection of Jesus at the Secular Student Alliance. In fact, I was one of only two Christians in a room packed with a handful of curious skeptics and a lot of convinced atheists.

The question-and-answer session that followed my presentation was scheduled for thirty minutes, but it ended up lasting almost three hours. Before it was over, we’d discussed not only the resurrection of Jesus but also how ethics derived from the teachings of Jesus have influenced religious freedom, care for the poor, and the abolition of slavery. Near the end of the dialogue, one student made his way to the microphone at the front of the room.

“I’m an engineering major,” he said. “When I’m making my calculations, all that matters is getting an answer that works here and now, in this life. It doesn’t matter what happened one thousand or two thousand years ago. But I actually like a lot of what you’re saying about Christianity. What I want to know is this: Is there any way I can be a Christian without believing Jesus was really raised from the dead? Is it possible to be a Christian without believing in miracles?”

I don’t think he’s alone in wondering about those questions.

It’s a common conception in certain locations and situations that, if you really think scientifically, you can’t believe in miracles and you certainly can’t take the Bible seriously.

In this post, I want to provide an easy-to-understand approach to thinking about science and the natural world as a Christian. This isn’t an academic article, and it isn’t intended to be—which is difficult for me, because everything in me wants to leap into a historical exploration of how modern science emerged from the seedbed of Christianity and how the notion of conflict between faith and science is a myth that emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries! And so, for those of you who may want to dig deeper into these issues, here are a few of my favorite books on this topic:

John Lennox, Can Science Explain Everything?

John Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World.

Melissa Travis, Science and the Mind of the Maker.

Theodore Cabal and Peter Rasor, Controversy of the Ages.

Why Scripture and Science Sometimes Seem to Conflict

Here’s what I want you to come to understand as you read this post: Scripture and science point to the same God; so, if Scripture and science seem to be in conflict, it could be because we’re trying to force one of them—or both of them!—to do something they weren’t designed to do. When I use the term “science,” I simply mean a study of natural world that makes observations, looks for explanations, and tests hypothesized explanations by conducting experiments.

The best place I know to begin an exploration of the intersection of faith and science is Psalm 19. C.S. Lewis called this psalm as “the greatest poem in the Psalter and one of the greatest lyrics in the world”—and, given his expertise as a literary scholar, I’ll take Lewis’s word for it. This psalm helps us to see both the potential of scientific knowledge and its limits.

The Natural World Declares God’s Glory

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the sky displays his handiwork. Day after day it speaks out; night after night it reveals his greatness” (Psalm 19:1–2).

We’ve all sensed this at some point.

Standing under a starry sky at night and recognizing how small we really are.

Sensing the beauty of a blue sky rich with clouds on a summer day.

Standing on the Big Four Bridge at sunset, watching the light glisten on the river and, in those few moments before you remember that the Ohio River is teeming with e. coli, being flooded with wonder and awe.

That sense of awe—what John Calvin referred to as sensus divinitatis—was designed by God for a specific purpose: to awaken our capacity to worship.

That’s what David was describing in this psalm. David wasn’t trying to provide a detailed scientific description of how the solar system works. He was writing a poetic response to the wonder of creation, rich with figurative language and language of appearances.

In the sky he has pitched a tent for the sun.

Like a bridegroom it emerges from its chamber;

like a strong man it enjoys running its course.

It emerges from the distant horizon,

and goes from one end of the sky to the other;

nothing can escape its heat. (Psalm 19:4-6)

The point of this text is not that the sun really sleeps or that the sun literally moves across the sky. David was using language of appearances, just like people do today. When someone asks, “What time is sunrise?” or “When is sunset?” you don’t say, “Well, the sun doesn’t actually rise or set; the earth turns and it only looks like the sun rises and sets.” If you do respond that way when someone mentions sunrise or sunset, you probably don’t get invited to very many parties.

When the Bible speaks about the natural world, the Bible speaks truth—but the Bible isn’t a science textbook. The Bible uses ordinary language to speak these truths. The primary point of these inspired words is to show us how the natural world can awaken worship within us. This capacity of the natural world is something that earlier generations of scientists clearly understood.

“To know the mighty works of God, to comprehend … the wonderful workings of his laws,” Nicolaus Copernicus wrote, “surely all this must be a pleasing and acceptable mode of worship to the Most High.” “The glory and greatness of Almighty God are marvelously discerned in all his works and divinely read in the open book of heaven,” Galileo Galilei echoed. According to Johannes Kepler, the geometric patterns that mark the created order are “a reflection of the mind of God. That men are able to participate in it is one of the reasons why man is an image of God.”

“God has written two books, not just one,” Francis Bacon pointed out. “We are all familiar with the first book he wrote, namely Scripture. But he has written a second book called creation.… No man... can search too far, or be too well studied in the book of God's word, or the book of God's works.” The Book of Nature declares the glory of God. King David grasped that truth in the ninth century B.C., and so have many other scientists and theologians and other scholars since that time. And yet, David also made it clear that there are limits to what the natural world can do for us.

The Natural World Isn’t Enough to Guide You to God’s Glory

The Book of Nature will never be enough to bring you into a relationship with God. That’s one of the reasons why God speaks to us not only through his world but also through his Word. In the second half of this psalm, David turned his focus from God’s revelation of himself in the Book of Nature to God’s revelation of himself in his Word, in the Books of the Scripture. The Word of God in Scripture does what the Book of Nature never can: through the Scriptures, God guides his people into a relationship with himself.

David hinted at this truth through the words he deployed to describe God in Psalm 19. When David was depicting the revelation that comes through the Book of Nature, he described God as El, the generic word for a divine being (Psalm 19:1). When he changed his focus to the revelation that comes through the Books of Scripture beginning in Psalm 19:7, David also changed the word that he used to describe God. In these verses, God is described using his personal name, his covenant name—YHWH, which is rendered in most of your Bibles as “LORD” (Psalm 19:7, 8, 9, 14). This is the name that the Israelites connected with the response that the Lord God gave when Moses asked what his name was. God’s response was, “I AM THAT I AM” (Exodus 3:14); thus, his name became his refusal to be named. That’s how David described his God once he turned his focus from God’s revelation in nature to God’s revelation in Scripture.

The natural world provides us with a message about God; Scripture gives us a word from God that can guide us into a relationship with him. That’s one of the reasons why David described the Scriptures in such exalted terms in the second half of this psalm. The Word of God renews us, it is right for us, it is radiant, and it is reliable (Psalm 19:7–9). The Scriptures are, according to David, as precious as gold and as sweet as honey (19:10).

This is not to suggest that the natural world is not wonderful and glorious—it certainly is! The study of the natural world brings us life-saving medicines and life-giving beauty. The universe is teeming with animals still to be discovered and solar systems yet to be named by any human being—and all of this is glorious. Yet none of these glorious realities can bring us into a relationship with our Creator; only the Spirit of God working through the Word of God can do that.

We and the Natural World Are Groaning for a Glory that Is Yet to Be

All of this talk about the glories of nature and the Scriptures should bring up a significant question in our minds: If there is so much glory declared in nature and so much truth available to us in Scripture, why don’t we live in constant delight at the glory of God all around us in nature?

The problem isn’t with the message that God’s world is sending out to us.

The problem certainly isn’t with God’s Word.

That’s the point David was making when he cried out,

Who can know all his errors?

Please do not punish me for sins I am unaware of.

Moreover, keep me from committing flagrant sins;

do not allow such sins to control me.

Then I will be blameless,

and innocent of blatant rebellion. (Psalm 19:12–13)

Sin has distorted our perceptions and our habits and our desires until we don’t even know all the ways that we have sinned. “Who can know all his errors?” David asked. “Please do not punish me for sins I am unaware of.” Sin has touched every part of who we are, to the point that our bodies don’t always desire according to God’s design and our minds are sometimes unable to see reality rightly.

Our depravity runs so deep that we can become so focused on the created order that we forget the Creator. The North African pastor Augustine of Hippo put it like this: “I asked the whole universe about my God, and the universe answered, ‘I am not God but God made me….’ Yet how many times am I focused on the lizard catching flies, or the spider entwining them in her web? I do proceed from there to praise you, but that’s not where I start.”

Sometimes, we can become bored with the glory that God’s creation declares. Years ago, when I was a student minister in Tulsa, I took a group of youth on a mission trip to Phoenix, Arizona. We left in the church van on a Wednesday night and took turns driving fourteen hours, all the way to Arizona. The Game Boy Color had just been released, and there was one student who had one. All the way from Oklahoma to Arizona, all he did was to play his Game Boy—while riding, while eating, while walking to the restroom at rest stops. Stunning scenery surrounded us all the time, but he wasn’t seeing any of it. On Thursday afternoon, we stopped at the Petrified Forest National Park and the Painted Desert, and I decided he was at least going to see this. I was certain that he would be in awe, if he would just look at it. So I made him leave his Game Boy Color in the van and walk a short loop looking at the Painted Desert.

When we reached the end of the trail, I asked him, “What did you think of that?”

His only response was a shrug of the shoulders and a question: “Did we actually come all this way just to see dirt and rocks?”—and he went back to his Game Boy Color, more impressed with eight bits of color than with the grandeur of the natural world.

If we’re honest, we aren’t much different at times. It may not be a Game Boy that blinds us to the glory of God in the natural world. It may be our busy-ness, our stress, our social media. Whatever the cause, we forget that the cosmos is constantly calling out the glories of God.

Because we do have a relationship with the very God that creation declares, Christians of all people should delight in the natural world, because God delights in his created order. British journalist G.K. Chesterton made this point so beautifully in his book Orthodoxy:

When [children] find some game or joke that they specially enjoy… they always say, “Do it again”; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead. For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, “Do it again” to the sun; and every evening, “Do it again” to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that he has the eternal appetite of infancy.

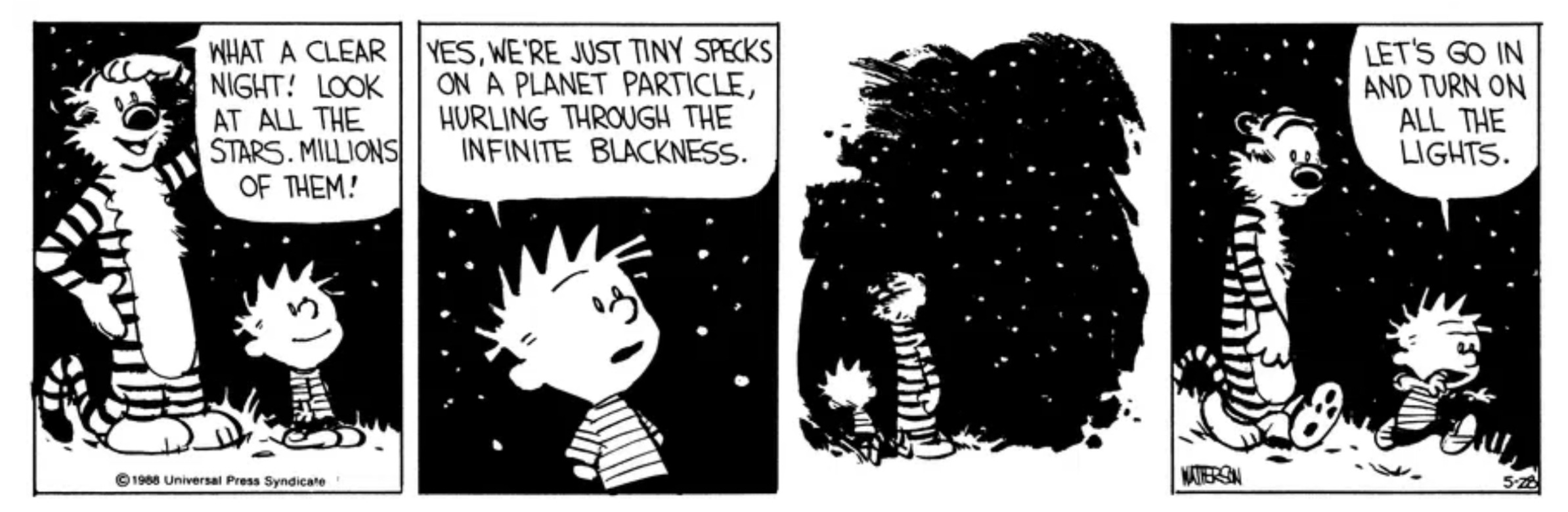

The wonder of the natural world reminds us that we are small compared to the universe, that we are not God, and that we are not in control. A few decades ago, the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes acknowledged this reality, perhaps without the author even recognizing it.

“What a clear night!” the tiger says. “Look at all the stars. Millions of them!”

“Yes, we’re just tiny specks on a planet particle, hurling through infinite blackness,” Calvin acknowledges and then stares into the sky for a few moments before it all becomes too much. That’s when he says, “Let’s go in and turn on all the lights.”

When I am sitting in my recliner with my remote control and all the lights turned on, I can feel as if I am in control.

Not so when I consider the vastness of the created order.

Yet sin has so infected our natures that we are blind at times both to the sins within us and to the glories of God around us. I think that’s part of the reason why David closed the psalm with these words:

May my words and my thoughts

be acceptable in your sight,

O Lord, my sheltering rock and my redeemer. (Psalm 19:14)

This is not a throwaway concluding remark. David’s words are a desperate plea for divine mercy. David has acknowledged that he doesn’t even know all the ways that he has sinned, so he cries out to God, “Let me be acceptable to you”—but he knows that his efforts will never make him acceptable and that his only hope is divine redemption, so he addresses his cry to “my sheltering rock and my redeemer.”

When we recognize how blind we are to the glories of God, we groan for a glory that is yet to be—and creation itself groans with us. That’s what Paul was describing in his letter to the Romans:

For the creation was subjected to futility—not willingly but because of God who subjected it—in hope that the creation itself will also be set free from the bondage of decay into the glorious freedom of God’s children. For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers together until now. Not only this, but we ourselves also, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we eagerly await our adoption, the redemption of our bodies. (Romans 8:20–23)

When sin entered into the world through Adam and Eve, all creation was infected with sin, and we became blind to the glories of God. The answer to this groaning is the gospel of Jesus Christ. On the cross, the punishments for all the distortions and degradations of sin were poured out on Jesus. The groaning of the entire created order became his groaning, his agony, his pain. But the death of Jesus was not the final word. Three days after all the pain of all creation fell on him, glory filled that tomb, and a new world dawned. We and all creation are groaning—yearning—for that moment when the glory of Jesus Christ fills the earth like waters flooding the seas, and we will glimpse the glory of God forever.

How Can These Truths Help When Science and Scripture Seem to Conflict?

What I’ve tried to provide here is a framework for Christians to think rightly about the natural world. With all of this in mind, I want to return to a point I made at the beginning: Scripture and science point to the same God; so, if Scripture and science seem to be in conflict, it could be because we’re trying to force one of them—or both of them—to do something they weren’t designed to do. Whenever you try to force something to do what it was never designed to do, the results are rarely what you intended.

A few months ago, I was upstairs in one of my children’s rooms, trying to figure out why a picture had fallen. The problem was that the nail was the wrong size for the hanger on the back of the piece of art. For some reason, I had gotten a larger nail, but I forgot to pick up a hammer—which was two whole floors down, all the way in the basement. By the time I pulled out the smaller nail with my fingers, the basement hadn’t gotten any closer to the top floor; it was still two floors down and two floors back up. So I did something that made complete sense to me at the time: I used my phone to hammer in the new nail. The nail went in just fine—but then I looked at my phone case, and for some reason, the case wasn’t all there. There were pieces on the floor, and there were pieces in my hand. That’s when something occurred to me that should have occurred to me a few minutes earlier: Maybe phone cases aren’t designed to be hammers. In fact, I suspect that the designers of the phone case never even tested it as a hammer. It probably never crossed their minds. Or maybe it did cross their minds, but they thought, “No one would be foolish enough to try to use this as a hammer.” But here’s the fool who did. Whenever you try to force something to do what it was never designed to do, the results are rarely what you intended.

That’s true not only when it comes to phones and hammers but also when it comes to science and Scripture. So let’s try to build on what I’ve written in this post and consider some ways that people try to use science or Scripture to do things they were never designed to do.

How might people try to make Scripture do what it was never designed to do?

The Scriptures do speak about the natural world, and whatever the Scriptures say about the natural world is true. But the purpose of the Bible is not to provide precise scientific details. Yet sometimes that’s what we expect the Bible to give us. One example of this is the way in which people sometimes try to force the Bible to provide us with details about the age of the earth—whether the world is thousands of years old or millions or billions of years old.

But that’s not the primary point of the opening chapters of the book of Genesis. The creation stories of the nations surrounding Israel depicted multiple gods going to war and claimed that the cosmos emerged from the bodies of the gods. When Moses wrote Genesis inspired by the Spirit of God, he tells a completely different story. The God of Israel is sovereign and separate from his creation; the cosmos is not a result of chaos or conflict, it comes from God’s good and perfect design. The point of the account of creation is to show how the true story—the story that comes from the one and only true God—is the story of an orderly creation with human beings, created male and female, as the crown jewel of the cosmos. Those six days of creation might be six solar days that happened a few thousand years ago, or the days might be figurative language depicting six ages of time, or they might be a literary framework, or they could be something else.

Throughout the ages, Christians have persistently taken different perspectives on this point. Augustine of Hippo thought God created the entirety of the cosmos in a single instant and that the six days must be figurative: “The Creator, about whom the scripture told this account of how he completed and finished his works in six days, is the one… who created all things simultaneously.”

Nineteenth-century Baptist pastor Charles Haddon Spurgeon took a very different view. He thought that millions of years may have passed between God’s initial creation of the world and the first day of creation. In a sermon preached four years before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, Spurgeon declared, “We do not know how remote the period of the creation of this globe may be—certainly many millions of years before the time of Adam.” C.S. Lewis thought that the six days of creation represented eons of time, and Tim Keller took a similar point of view, for different reasons and in a different way than Lewis. All of these individuals were faithful followers of Jesus, they believed in a real historical Adam and Eve who sinned against God, and they expected that God will make all things new at the end of time. Yet they took very different perspectives on the age of the earth. This should help us to recognize humbly that the Bible isn’t trying to give us scientific details about issues such as the age of the earth. When we try to force the Bible to give those details, we’re using our phone as a hammer.

How might people try to make science do what it isn’t designed to do?

Science is wonderful and important—but, sometimes, people seem to take the perspective that science can eventually explain everything. That’s simply not true. In the first place, science is only able to explain how things are not how things ought to be. Science tells us what is, but it can’t tell us what should be. It’s the most famous line from the original Jurassic Park: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

Since science is the study of the natural world, science cannot explain everything, unless you presume from the outset that the natural world is the only world there is. And yet, there are scientists who claim that science is able to rule out every possibility of God and miracles. According to Oxford University biologist Richard Dawkins, “Any belief in miracles is flat contradictory not just to the facts of science but to the spirit of science.” But science is a study of the natural world whereas miracles are supernatural—which means that science cannot rule out a miracle. A miracle isn’t a violation of the laws of nature; a miracle happens when the Creator intervenes in the laws of nature. Part of the point of a miracle is that it doesn’t happen according to the ordinary course of the natural world.

In fact, the sheer orderliness of the laws of nature is difficult to explain unless there is an intelligent and personal Creator. “I do not deny that science explains, but I postulate God to explain why science explains,” Oxford University philosopher Richard Swinburne has written. “The very success of science in showing us how deeply orderly the natural world is provides strong grounds for believing that there is an even deeper cause of that order.”

Right now, an exhibition of Ethiopian sacred art is being displayed in the gallery of the church where I serve as a pastor. Imagine a scenario with me for a moment. Suppose that I studied these beautiful pieces of art until I knew every detail of every piece of wood, leather, parchment, and hammered metal in this exhibition. Imagine that I researched the inks and the brushes that produced every stroke of paint. Now suppose that, after all of that study, I declared, “I know exactly how each of these pieces of art was made; therefore, since I understand every detail of these paintings, there must not have been any painters.”

If I were to make such a claim, you would conclude (rightly!) that I am arrogant, irrational, and possibly insane. Knowing how a painting was made doesn’t mean there was no painter. On the contrary, if I understand the paintings, that knowledge should increase my appreciation of the skill of the painters. It’s equally absurd for anyone to claim that our comprehension of the cosmos rules out the work of a Creator. “The heavens declare the glory of God”—and knowing how the heavens and the earth are made should multiply our awe in response to the Maker’s glory.

Delight in Both Books

“Is it possible to be a Christian without believing in miracles?”

That’s what the engineering student at the Secular Student Alliance asked, and my answer ran something like this: “If the resurrection didn’t happen in real life, nothing else about Christianity really matters.”

What I said was true—but if this same student were to ask me the same question again, there’s something else I would add: “Have you ever considered why your calculations work at all? Why do we live in a cosmos with a deep and elegant underlying order that seems to extend throughout our universe? What if your very calculations only work because we live in a cosmos that is declaring the glory of God?”

God speaks to humanity through two books: the Book of Nature and the Books of Scripture. Learn to delight in both books. Revel in the Book of Nature which fuels our worship and praise, and rejoice in the unerring Books of Scripture that guide us into fellowship with God by calling us into the story of his redemptive love.